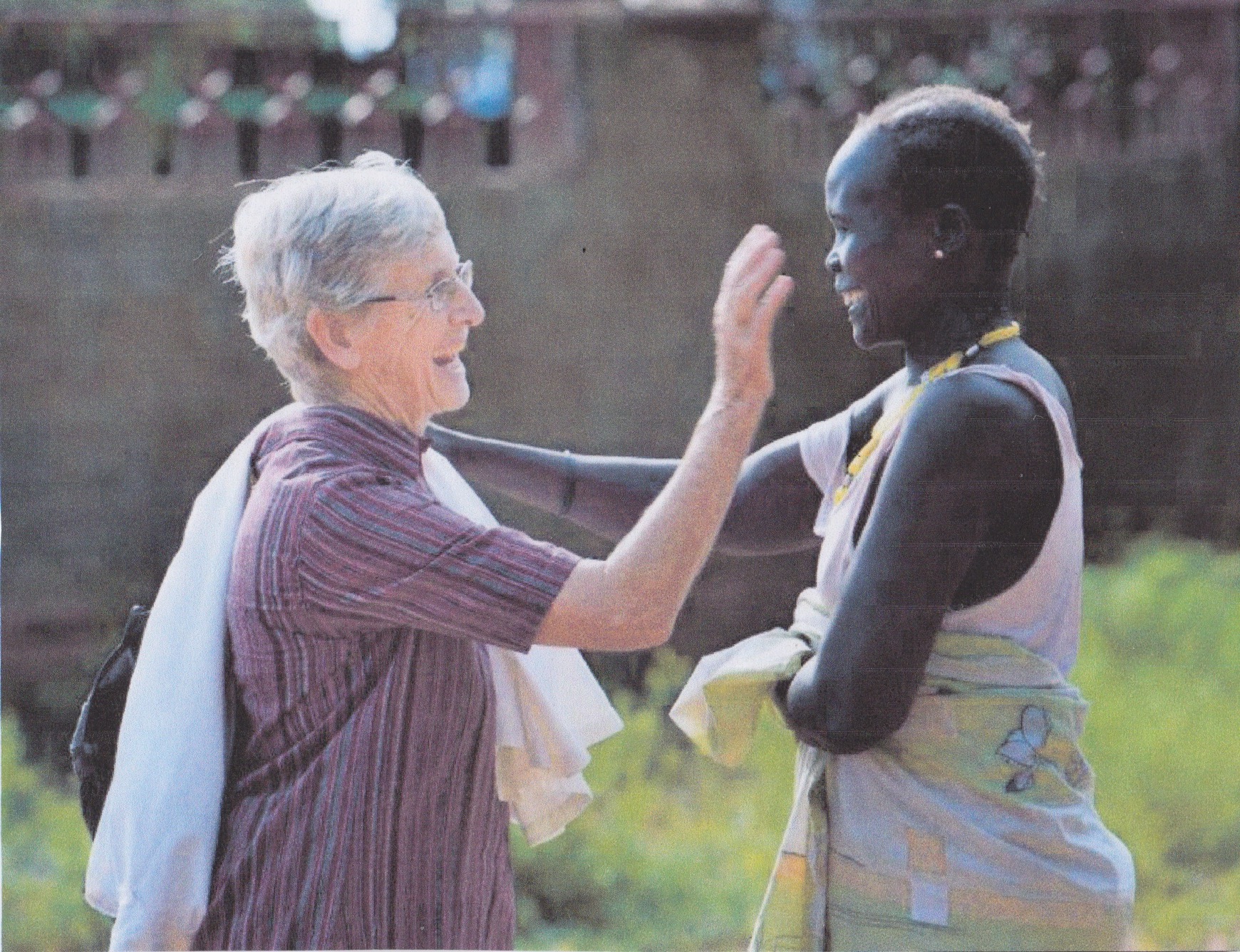

Her full name is Sister Dorothy Anne Dickson of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Mission, but I know her as Auntie Dot.

The following is a transcription of an interview she gave with my cousin, Pastor Joseph McCauley. The interview formed part of a regular Sunday service at St Luke’s church, which Joseph founded with his wife, Lisa, in Tauranga. You can also listen to their conversation.

As a family, we are thrilled Joseph managed to get some of Dot’s life on record because she is modest and hardly thinks it worth the trouble. Yet it seems a chapter could be written about every sentence of this interview, and a novel written about every month of her life – if she saw fit to recall every detail of her remarkable story.

♥♥♥

Joseph: Dorothy’s here from South Sudan and I thought I’d take the opportunity to interview her, and get her to tell a little bit of her story for the simple fact that we might be inspired and challenged and provoked in regards to our own life.

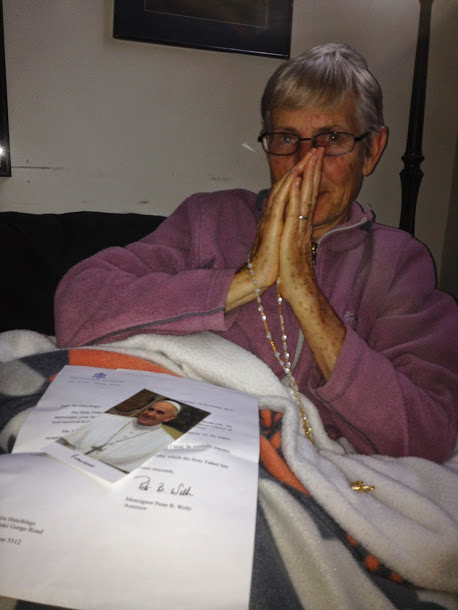

How long have you been a nun? 48 years

We celebrated Dorothy’s 68th birthday last week. I don’t want to give away her age but that’s the birthday we celebrated. It’s my understanding that while the Sisters of Our Lady of the Mission work within the broader stream of Catholic theology, there’s a few foundational thoughts or ideas behind their particular order of nuns. I’m going to read a couple of these thoughts and then chat with Dorothy about it.

The mission you engage in and refer to is about the Trinity: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit of God at work in the world – reaching out to creation, healing and reconciling that the father sends the son, who sends the spirit, who sends us into the world to be the hands and feet of Jesus.

That mission thus becomes a way of life, a way of contemplation, a way of love, and even as there’s no boundaries within the Trinity, there’s no boundaries in regards to the places or spaces that your order of sisters would travel to be the hands and feet of Jesus.

Anywhere in the world where there’s need. Essentially you focus on the poor of humanity, and that mission becomes an incarnational thing: your spirit goes alongside your hands and feet in the very places where those people are.

I think that’s beautiful. It’s well articulated and it resonates with me and us at St Luke’s. I guess when you were younger, 16 to 17, was it this beautiful theology that drew you to become a nun and go down that path? Or is that something you discovered later on? How have you come to be a nun? What was the process that brought you to taking your vows?

Dorothy: Certainly it wasn’t the theology. Its like a relationship when you get married you have no idea what you’re going to be living out and its something that you learn to live out each day. So I’m a Sister of the Lady of our Missions. I mainly grew up in Taneatua but I was sent to Hamilton to Sacred heart Girls College as a boarder for my secondary education. I grew up during the Vietnam War so protesting against the Vietnam war became something that was quite important for the generation that I belonged to.

I often asked myself if you are sending soldiers, why aren’t we sending missionaries, why aren’t people going to reach out to these people who are being so hurt in war?

And in my last years in school I read books of Thomas Dooley, who was a Catholic marine/DR who was there in Vietnam when it was divided into north and south in 1956. So he received a lot of the people fleeing the north to move to the south and then he went to Laos and Cambodia and mainly he worked at training midwives, village midwives, and giving them a suitcase in which they had what they needed to have safer deliveries out in the villages. And it was actually his life and his ideal of being out there that awoke in me a kind of call to work in places mainly of war and famine. The Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions had missions in Vietnam so there you are, I though, you join them and you can get to Vietnam.

So then you go through this process. The first, I was 17 when I left home. You wouldn’t do it now – I wouldn’t do it now – but at that time everyone went off at that age to training college, or to train as a nurse, and most of the girls that I went through school with were married by the time they were 20 or 21. That’s how life was. So I went to Christchurch. There were six of us who went down that year. And our first year was just a year of training where you work. We helped in the schools. We looked at what this religious life was about. And then make a decision whether this is what we want to go on with and the congregation looks at us – and says yes, or no – so after a year as what we call a postulant then you become a novice and for two years then we are a novice.

The first year there is just totally spiritual training – learning to pray, learning to contemplate, doing scripture study, pastoral studies, trying to understand mission and to understand the theology of religious life. At this time in the Catholic church, it was Vatican too so it was a time when many things were changing and old traditions were being looked at again, and new ways of being present were also being looked at. Then after two years, so by this time I am 20, you make a decision to go on or not to go on. And at that time we would take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience for one year and then again you have another time, another year and then another time, another year for up to five to nine years before you make a final decision with the community that you are living with to either take your vows, final vows.

So it’s quite a long engagement period and you have plenty of time to go in and out of it. I was 26 when I made my final vows in Hamilton. You have these vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, and when you enter you kind of think: Okay right, nothing belongs to me. Ah chastity, okay, so I’m not going to be married – I’m going to live my relationships within community. And obedience, whatever I’m told to do, if it sounds okay with God, that’s what I’ll be doing. So I’ll go to wherever I’m sent and I will do the work that I’m asked to do. And that’s kind of like scraping the surface, it’s like I’ll love you forever. And then you grow into that and it takes time and each year the whole meaning of these vows become different.

When you try and understand poverty when you are living with people who have nothing, and you find that even your own education is a wealth and your ability to move. I lived in a village in Senegal which was five kilometres from the sea. The majority of people had never seen the sea. The majority of people knew nothing outside the village that they grew up in and that was as big as their world was. So what poverty do I have there, when I know so much more because of my education, because of my experiences, because I have been able to see and learn from so many other things.

Then you find actually when you go on mission and everyone thinks this is fantastic, and you are doing wonderful things, you actually take yourself. You take your anger, your impatience, your desire to be understood.

And you live through the frustration of people not understanding when you are trying to speak in their language, with people who have no idea what you are there for as a religious person. Like, why aren’t you married? Where are your children? It depends on the communities that you live in.

And you find your own poverty in yourself when you don’t understand what is being said to you, when parents bring you children who are dying and your first question, which you have to kill, is why on Earth did you not come earlier? Why are you asking me to do something now when it seems so late, when you’re wanting something which is beyond what I can do? And you find your own impatience there and you know your own poverty. And you know that you can not do this alone, you need community to be with you.

And the same with obedience. Is it to try and find each day, what is God asking me to do this day? And God’s not there to write it out on a note and say, this is it. You have to find it in the community where you are living and the people who come to you that day. In the life that’s going around you, and in the community, you have to struggle to hear and find what it is that is for me to be the presence of Christ here today. And that also is a huge challenge. And is the challenge for everybody.

And then to take a vow of chastity, which for us means that we are celibate, and we do not have children but you are still called to love and you are called to love this person who may not like you. You are living in a community with people who might annoy you at times, and you are asked to reach out to people and to find how to be the love for those people, and it is not easy. And it is a challenge all of us have to live through.

We all have to live through our own poverty, through our own finding of what it is we are called to be in this world, and in our own learning to love in whichever way we have been called to live love.

Basically that is what our three vows are about and they are not something you know when you take them, the same as when you get married, you have no idea what you are going to live through. And so the same for us and it is something that we need to work with each day and to try and find the way. That’s how it is.

Wow. I guess a lot of people would say that becoming a nun is a pretty radical decision, or a pretty sacrificial call. Do you think sometimes as Christians we have domesticated Gods voice, or God’s call, and we tone it down to be the things we want it to be, the things that are more convenient?

I think we do. I mean, even in the congregation we live in: it is 150 years old. It started in France with the first sister in 1861, and in 1865 the first five sisters arrived in Napier in New Zealand and they came – one from England, four from France – to live in Napier and that was their mission: to go. But then during the years of the First and Second World Wars, when there was less travel, that idea of going overseas got lost within the congregation.

We grew a lot in NZ but then we were called to look at, what are we here for? What is our mission to be? And so we found we needed to go out again and to reach out again and not just to… Like, we had big schools, many sisters, but suddenly, is this what mission is? We had to move out from that and to find, no, maybe there are other people that are needing us now and so all of our schools have been taken over by lay teachers, who are doing a wonderful job, and we ourselves have moved to working with new immigrants to working with budgeting in some of the poorer areas.

We are challenged not to get into the establishment where we are secure, but to look again and to move out again.

And as a congregation it is the same over the last few years. We have moved to Taiwan, to Laos, to Kazakstan, to Bolivia, reaching out to other people in other areas, and our missions in Vietnam, Myanmar, India, the Philippines have all moved from the big schools that we had – because our main work was education – out into the villages to literacy programmes, to development programmes with women. We left the schools to those who have been trained and are able to take over and to continue the work, while we free ourselves to go out into the further away places where there is less help. And I think that’s a challenge for all of us.

Speaking of further away places, you’ve trained as a teacher, you’re trained as a nurse, and you’re trained as a midwife, and those are the different skills that you’ve used in the world. Where are the different places that you’ve lived throughout your life?

After I took my first vows, I trained as a teacher in Auckland and I taught for two years in Hamilton and then three years in Waitara. But I was asking all the time: Can I go? Can I go? Can I go? And it was offered that I could go to Vietnam. I was lucky at that time. I was in Taranaki and in the hospital there, there were two doctors who were part of medical teams in Vietnam, and they said I could go to hospital. They put me in a surgical ward – and they got the nurses to teach me how to give injections, how to do dressings, how to sew up wounds, all kinds of skills that they said: ‘It doesn’t matter what you do in Vietnam, you’ll need these skills.’

So I did that and then I went to Vietnam and I thought, this is where I’m going to be for the rest of my life. But that was 1974 and in 1975 was the fall of Saigon and the Viet Minh moved down and the whole of the country was reunited with the north. And so at that time, I left. I returned to New Zealand and I trained as a nurse at Auckland Hospital then I left and in 1980 I arrived in Senegal, in West Africa, to take over the running of a very big clinic that our sisters had there.

And I came from Auckland Hospital, where you’ve got all these doctors, and people who know more than you do, and all the equipment, and you end up in a village where there’s – you’re the end of the line. And there’s nobody above you to refer to, and suddenly you are responsible for all of these people. And you think, mmhmm, maybe this person’s really sick and should be in hospital so you suggest to the family that you take them to hospital, which is 50 kilometers away, and then you find they think, if you say to go to the hospital, that means you’re going to die, because that’s the only thing that happens in a hospital. So they go home and they die.

And you’re kind of well, mmm. So you open up a small ward and you start taking on the care of people far beyond what we would normally do in an out-patient situation in New Zealand. And you are challenged to learn more and to develop more skills and just gradually expand into taking care of these people. So, I worked there for 13 years. By that time, the team that I had worked with, two of them had gone down and trained and got their diplomas as nurses and they were able to go and take over the clinic. And the same team, they are still there, looking after exactly the same people – except that the clinic has changed from being a general medicine and vaccination and midwifery centre into being the major HIV centre for the area. So it does all the diagnosis and follows up the treatment of HIV people because the government itself has developed more clinics to take over the general medical care.

So I left there and I asked of the congregation if I could return to working in places of war and famine, where our sisters were not able to go.

And so I joined a French aid organisation called Action Against Hunger and I went to Liberia for one year. There, first of all I was doing vaccinations programmes. There had been an epidemic of measles, out on the side of Liberia that was held by Charles Taylor, and in one village, for example, 200 children had died of measles. And so they asked us to set up the vaccination programme. Then from there I moved onto training the traditional birth attendance for the villages.

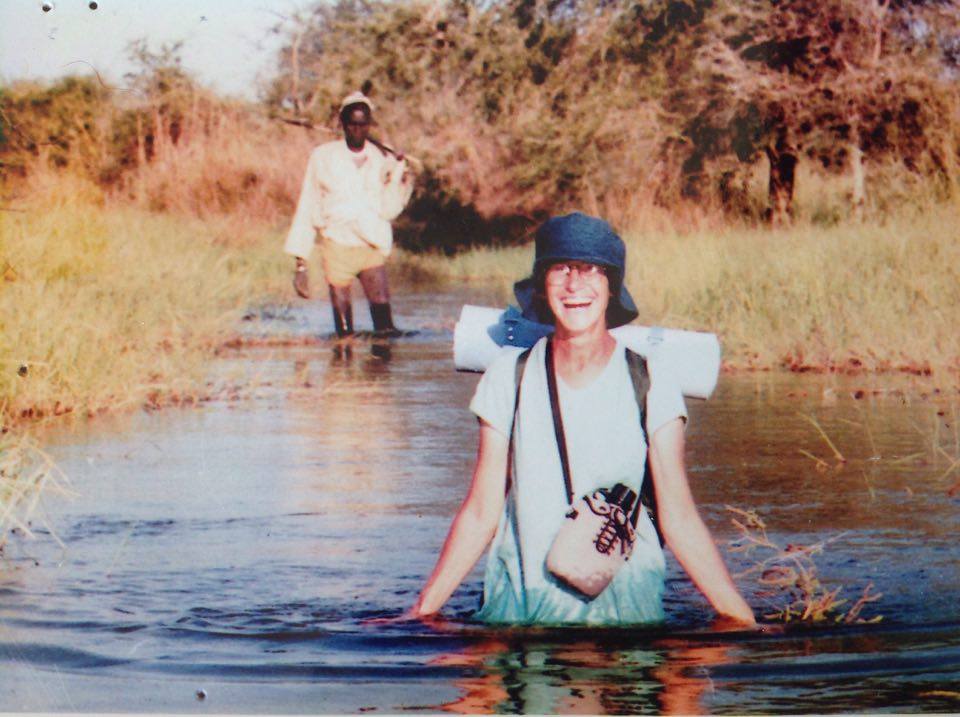

After that, I had asked if I could go to either Somalia or South Sudan and in 1994 I went to South Sudan and I worked there in displaced people’s villages where people had been bombed from the camps they were in and moved to other areas. I worked out in the swamp area of the Nile River, where there are no roads and you walk everywhere, and I was looking after 11 clinics there.

Then I came back to NZ and I was pretty shell shocked and depressed and I was in the Ashburton Hall therapeutic community for over two years, getting myself back together again, working through some of the trauma of Vietnam and of living in war areas.

Then I trained as a midwife and I returned to South Sudan on and off until 2006. I was back there full time, working in centres for severely malnourished children and from there I moved to Darfur, where I worked for another two years until Omar al-Bashir was indicted for crimes against humanity for what had happened in Darfur. And so we had to leave the country within a very short period of time.

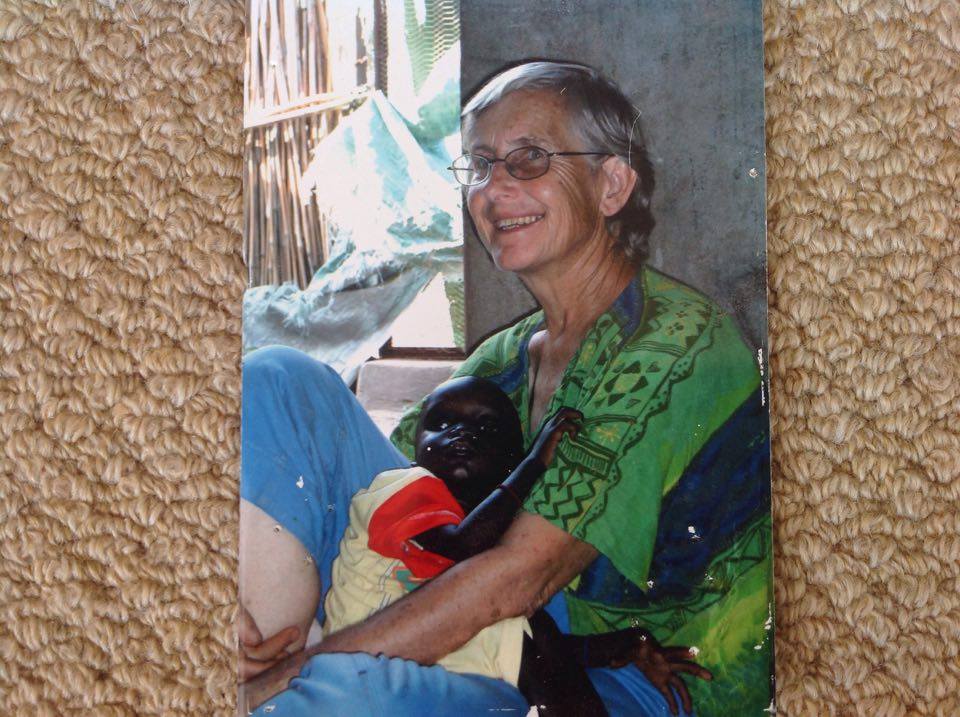

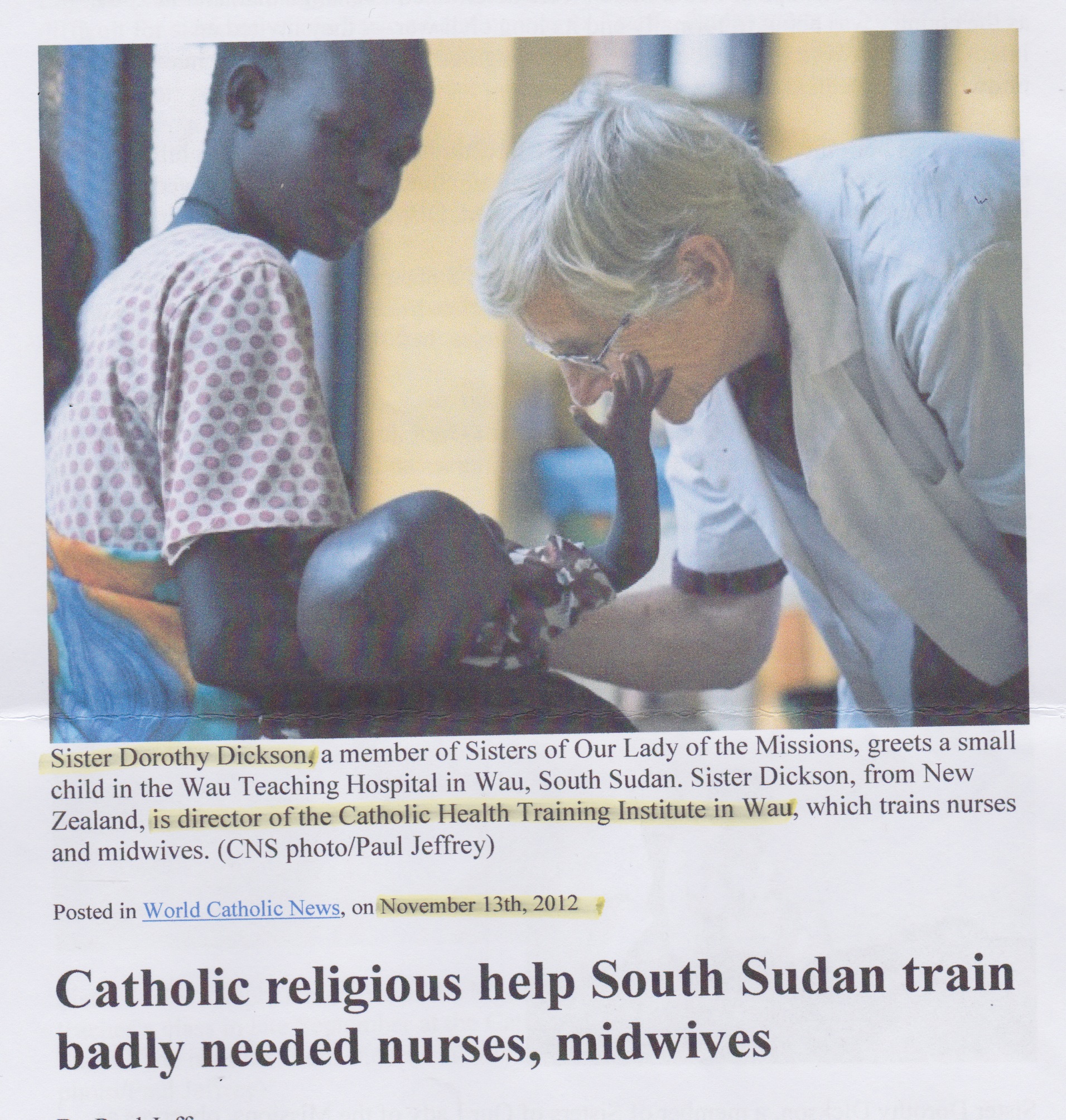

From there I went to Chad to work in the malnutrition section of the hospital, near the border where lots of refugee children were coming from Darfur. And then from there I am now in Wau, in South Sudan.

Let me pick up on two of those spots. I know when you were serving in Vietnam you ended up being taken prisoner by the Viet Cong for a period of time. Eventually you were released. Does that kind of experience shape your resolve to work in war-torn countries? Or to even be a nun? How did you reconcile that?

I remember the town that we were living in was up by the border with Cambodia and it was the first province that fell to the Viet Minh. It was around Christmas. There had been a lot of bombardments and the Viet Cong and Viet Minh had come into the town during the night. That morning we left the town and I can remember seeing all these people who thought that they would be defended by the army of South Vietnam and who weren’t defended. The army left during the night and left the people unprotected and undefended. And they didn’t know what to do so they decided to walk.

I remember being there and thinking these people are like sheep, without a shepherd. There was nobody to lead them. We walked for about eight days. But along the way I came upon a soldier, a South Vietnamese soldier who was dying. And I stayed with him but people kept saying: ‘You have to come, you have to come. Otherwise we’re going to be caught by the Viet Cong.’ And I stayed and I stayed and the last of the people are going and they say: ‘You need to come, you need to come. You have to leave him, otherwise you’ll be lost.’ And I left him. And that is something I need to live with. And I don’t want to leave people in those situations again. And so I go back.

Wow. I know it’s moving as well, your flight out of Vietnam. Tell us about that, on the Hercules, and who you had with you.

Up in Phuc long, we had children whose mothers had died in childbirth and we were looking after them during the bottle-feeding stage until they were weaned. And just before the fall of Phuc Long, those children who could go, returned to their families. But we had three children who were left. One of them, the family had been killed in a bombing of their village. Another one, the father of the child was not the husband of the mother and so she asked if that child could go. And another family, the mother was not there and there was no way they could take over these children. So three of the children, who were under a year old, went down to Saigon, with some of the sisters from Vietnam. While we stayed up in Phuc Long.

So when it became apparent that the whole of South Vietnam was collapsing, the Australian embassy was arranging the evacuation of orphans from the different orphanages, mainly small children. Children whose parents were American-Vietnamese, and so were not really well accepted within the community, and children who had polio, or were handicapped in some way. We went to the Australian embassy and they had said they would allow the three children who were with us to go. We found some of their relations in a camp and they said: ‘There is no way we can take these children into this camp, please take them with you.’

So we went to the Australian embassy and there was a bus with all these orphans on it. There were about 150 to 200 of them. And at that time the whole of Saigon was in panic and along the road as we drove out, parents were trying to push their babies through the windows of the bus. Because they were so afraid of what would happen when the Viet Cong came. So there were these unknown babies also coming into the bus. And we went to the airport and it was a Hercules transporter and the older children were at the front in nets; and on the whole bottom of it, there were cardboard boxes with twins – trying to keep the twins together in these cardboard boxes so they wouldn’t get separated on the journey.

And the pilot says: ‘Well, Sister, you’re responsible for getting us out of this airport safely.’ And I was like: ‘Yeah? Do I have a hotline to God?’

Because the last plane to leave was a big Galaxy 600, which was taking orphans to America, and it had crashed just after take off and no-one knew at that time whether it had been shot down by the Viet Min, or what had happened. It’s turned out that the door had not been correctly closed and it had swung open and so the pressure was lost. But at that time nobody knew. So we flew out, like that, to Thailand, where a big Qantas jumbo jet came with people to take the children onto Australia. So, that was how I left Vietnam.

We’ve been journeying through John’s gospel, and throughout John we see Jesus promising life, eternal life, abundant life, fullness of life, these kinds of things. And often we wrongly equate that with super-sized TVs or bank balances or careers or relationships, or the material stuff of life. I guess your vows as a nun say no to all of those kinds of things, which we often think will give us life. And yet all of the time that I’ve known you, I’ve found you to be somebody that sparkles with life.

I remember one Christmas we were enjoying a normal family Christmas at Nana and Pop’s house and suddenly Dorothy and one of my uncle’s burst into the room with two massive bags of styrofoam beanbag balls and they said: ‘It’s a white Christmas!’ And they started throwing beanbag balls and we had that many beanbag balls over the lounge floor we’re still finding balls the next three Christmases. In all photos your eyes always sparkle with light, I guess you could say. So how would you understand this life, this fullness of life that Jesus offers, and where do we find that?

I remember when I was in a refugee camp in South Sudan and I was saying: ‘Life is pretty depressing.’ There was a lot of death, a lot of insecurity. The living conditions were a bit horrific, with hordes of rats and flies. And I remember saying: ‘Just one smile a day, just to let me know there’s a presence here, one smile a day.’ And I think, ever since then, I keep looking for one amazing something that says it’s bigger than the pain. It’s bigger than the suffering. There is still beauty and love in our world. And it might be a bird. It might be a flower. It might be the way a mother picks up a child.

I was driving home one day and I turned and there was a shepherd with a sheep and he had a lamb around his neck. He was carrying the lamb. And I was talking to a mother with a big boubou on, which is a big West African dress, and suddenly twins, children, peeked out from either side. And in the camps, the children used to come up to me and they’d say ‘Kowai chukawaija Ayana Thataria’ [approximate romanisation], which means, they’d look at my eyes, and they would say, because my eyes are blue, and they are not used to that, they say our eyes are like the torches switched on and their eyes are like the torches switched off. Because their eyes are dark.

And all of those times, just finding that, yes, there is beauty, there are moments of blessing, there are people who care for each other in the saddest of situations. So, that’s where you go.

And, lastly, in terms of loving God with all your heart and loving your neighbour as yourself. What encouragement, or challenge, or advice would you want to offer a community like ours?

I think in the Catholic tradition and other traditions, when we go to Communion, which we believe is the body and blood of Christ, they will say: ‘This is the body of Christ.’ And it’s true, in my belief, but the person behind me is also the body of Christ, and the person in front of me and to either side. Everybody is the body of Christ. And it is to be aware of that.

It is to be aware that the body of Christ is bigger than this community. That the body of Christ is also in our Muslim brothers and sisters.

The body of Christ is right throughout this world and if we do not reach out to others, if we stay closed, in our own community, then we will not be the hands and the heart of Christ today. Because we have to go out so much more to others. And we have to go beyond our safe Christian communities, beyond the church that I belong to. Beyond and reach out to others. I was with a Muslim man in Senegal and we were talking about God and he said to me: ‘God, he is is near to me, he is the marrow in my bones.’ And I think we will find that if we speak to other people that everyone, everywhere, is reaching out to understand life in a better way for us and for our planet.

♥♥♥

The following was written by my uncle John Dickson, Dot’s youngest brother. In this piece he provides a Dickson family context for Dorothy’s life choices:

Our father Colin Dickson was manager of Opouriao Dairy Co-op Cheese factory in Tāneatua in Ngai Tūhoe country. He learned the cheesemaker’s trade at Edendale after leaving school, working in what had been NZ’s first dairy factory – his grandfather a founder of.

Most of the Opouriao factory staff were Tūhoe men, and Colin’s staff were amongst the first Māori to obtain their Boilerman’s ticket (a coveted qualification); their cheeses included Dutch varieties – Edam and Gouda for example (which was also unique in that era of Cheddar) and won prizes at Dominion Competitions in London.

The staff traveled to Auckland by train to see the 1959 test match between the touring British & Irish Lions versus the All Blacks at Eden Park (my father later had a season ticket – two prime seats in the A-stand which he retained until the 80s, and I used whilst at boarding school in Auckland). None had, so far as I know, been to the City before.

Dorothy and siblings (including your mom) attended Tāneatua Primary School, and had numerous Tūhoe friends. Rita Dickson was Akela of the local Cubs for a time. Some Reo Māori kupu (words) entered the vernacular of our family, and I recall my father greeting Māori men in Māori during my upbringing.

(I worked alongside two men, Henry Te Amo and Hina Temo, who had worked under my father at Opouriao, when I entered the Dairy industry in 1978 at Edgecumbe. They remembered and respected our whanau).

I mention all this because I believe that alongside her Catholic faith, Dorothy absorbed a sense of justice and equality (and hard work) as values which have informed her mission. In that sense, her life should be understood as less ‘saintly’ and more a product of whānau – and personal choice and sacrifice. I believe she’d agree.

I visited Dot in M’Boro, Senegal in July 1981 for a month. A further connection with Africa has been forged by Dorothy’s brother Edward who worked (from London with the ITF) alongside Union members across the continent during the 2000s, and my families enduring involvement in Mozambique 2000 through 2014. There’s a story to be told of our parallel connectedness with France, but that’s for another time perhaps.

‘Whānau can be multi-layered, flexible and dynamic. Whānau is based on a Māori and a tribal world view. It is through the whānau that values, histories and traditions from the ancestors are adapted for the contemporary world.’ Te Ara Encyclopaedia of NZ

♥♥♥

The following is a timeline of Dorothy’s movements, which she told me several years ago:

Balclutha, born, 31st October, 1947.

Featherston, 1948. (Pat Keene is mentioned here, but I don’t know why.)

Taneatua, 1950, primary school.

- In Featherston and Taneatua, their father made cheese and was involved with the Opouriau Dairy Factory.

Kawakawa, 1960.

Inglewood, 1962.

- From 1959 to 1963, she went to Sacred Heart Boarding School in Hamilton.

Christchurch Convent, 1964-66.

Auckland, 1967-68, Loretta Hall Catholic Training College. Living at Upland Road?

Hamilton, 1969-70, teaching for two years.

Waitara, 1971-73, teaching primary school new entrants for three years.

- She had a tea party for her 21st birthday at Upland Road and wore a black habit.

New Plymouth, met doctors who had worked in Vietnam and was taught first aid; did introduction to nursing school with intention of going to Vietnam.

Saigon, Vietnam, 1974. Dorothy was “named to go”, conscripted as a volunteer, accepted and was confirmed.

Phuc Long. Fall of Saigon. January 1975, captured for nine weeks with two others.

Sydney via Bangkok with orphans on military plane.

Waiotahi, New Zealand, homecoming party.

- She told her family: “Bury me wherever I die.”

Oponaki, June 12, 1975, taught primary for six months.

Auckland hospital, 1976-79, nursing training.

- In March 1979, she became a nurse and finished a BA in Education and Sociology.

Paris, France, December 1979, to learn French in preparation for Senegal.

Senegal, April 4, 1980.

- Dorothy stayed in Senegal for a total of 13 years. She went to Paris again in 1983, where she met her sister Helen. She visited NZ for a few months in 1987, during which we celebrated a white Christmas, thanks to the beanbag balls she and her brother Geoff threw over the living room at Upland Road in Tauranga.

- By 1993, other people could run the Senegal clinic. Dorothy volunteered to go to places of war and famine and was accepted by the group “Action Against Hunger”.

Liberia, which was never colonised, and was in the midst of civil war. She lived among the side of Charles Taylor.

The Congo, for one year. There was bombing and children with guns. Many AK47s.

Sudan, Lubone, 1994. Displaced people were attacked and evacuated.

- Dorothy recommends reading the book They Poured Fire on Us from the Sky to understand this time.

Sudan, Akar, 1995-96. Evacuated into the bush and flown out in planes to Kenya border by the UN, and into Lokichogio.

New Zealand, Ashburton Hall, mid 1997-mid 1999. To deal with accumulated post-traumatic shock.

Auckland, 2000, nursing at Middlemore Hospital, living in Panmure.

Auckland, 2001-02, midwifery at AUT.

Sudan, Bantiu, 2002 for six months.

Back in NZ, served on the leadership team for sisters.

Sudan, 2004 for three months.

Sudan 2005-06.

- Dorothy said she chose Sudan because of the struggle and because she liked the people.

Sudan, Darfur, Al Fashir, 2007-09, she moved from the town to camps with canvas and mud blockhouses.

Back to NZ for March and April.

Sudan, August 2009-Oct 2010.

NZ, Nov 2010-April 2011, training.

Sudan, Wau, July 9, 2011, South Sudan gained independence and Dorothy gained a three-year contract with Solidarity with South Sudan.

- She spent years training midwives in Wau, South Sudan, and there is still much conflict in the area.

2021: Dorothy moved back to New Zealand and lives near family in the Bay of Plenty. She is studying the Maori language and adjusting to life.

Nicely done, and very much appreciated E. Beth Allan.

Thanks, John! Your comments are extremely insightful and interesting!

Wow so special, well done.